Large language models' impoverished theory of cognition

Language models fail to understand because they don't even try.

Between a problem and its context

Christopher Alexander, in Notes on the Synthesis of Form, develops a theory about goodness of fit: the match between the form of a problem context and the form of a solution. In the introduction, he contrasts the 'un-selfconscious' process of design suited to problems with lower complexity and more external constraints with the self-conscious process of design intended to address high-complexity problems with far fewer environmental constraints. An example of the former might be carving a piece of wood into a decorative handle, and an example of the latter would be planning a neighborhood in a city. In the former, the immediate feedback of a blade on wood gives the carver proprioceptive knowledge of the material structure of the problem - a knot will be more difficult to carve, and may need to be incorporated into the final shape rather than being carved off. Designing a neighborhood is not the same kind of problem: the range of problems, material and social constraints, and possible solutions is almost immeasurably larger. Hence the need for diagrams, schematics, tables of data, and other methods of organizing information in such a way as to make the problems at hand tractable.

He goes on to discuss why that process of self-conscious design, despite its aims, remains wholly inadequate for dealing with problems of such complexity. In the process of design, the designer 'invents concepts to help himself decide which subsets of requirements to deal with independently.'

Now what are these concepts, in terms of the system of variables? Each concept identifies a certain collection of the variables. 'Economics' identifies one part of the system, 'safety' another, 'acoustics' another', and so on.

My contention is this. These concepts will not help the designer in finding a well-adapted solution unless they happen to correspond to the system's subsystems. But since the concepts are on the whole the result of arbitrary historical accidents, there is no reason to expect that they will in face correspond to these subsystems.

Alexander contends that a designer's primary difficulty in mapping solutions to problems arises from the fact that conceptual terms and abstractions have an extremely tenuous relationship to the material form of the problems the designer attempts to solve.

Take the concept 'safety', for example. Its existence as a common word is convenient and helps hammer home the very general importance of keeping designs danger-free. But it is used in the statement of such dissimilar problems as the design of a tea kettle and the design of a highway interchange. As far as its meaning is concerned it is relevant to both. But as far as the individual structure of the two problems goes, it seems unlikely that one would should successfully identify a principal component subsystem in each of these two very dissimilar problems. Unfortunately, although every problem has its own structure, and there are many different problems, the words we have available to describe the components of the problems are generated by forces in the language, not by the problems, and are therefore rather limited in number and cannot describe more than a few cases correctly.

I could not resist the connection between what Alexander was saying and the follies of the recently overhyped large language models like GPT-3. ChatGPT has been notorious for being unable to see how words appropriate for one description do not apply to a different object in a different context.

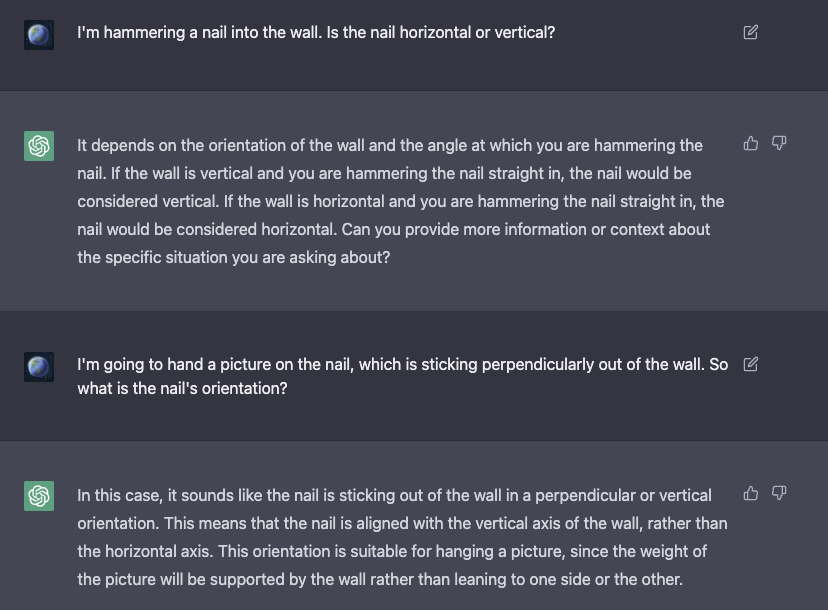

Thus, it is far more susceptible to this limitation than human users of lanugage are. The corpus of errors being assembled in the ChatGPT/LLM Errors Tracker by researchers Ernest Davis, Jim Hendler, William Hsu, Evelina Leivada, Gary Marcus, Vered Shwartz, and Michael Witbrock has many examples of basic failures of meaning, usage, and compositionality that should be sufficient to puncture the hype surrounding LLMs' ability to describe the world. The question of how to hang a picture seems to be about as simple as many design problem gets, but ChatGPT cannot help you with it:

The model both fails to pick up obvious contextual information about walls from ordinary use - that they are vertical - and does not understand that something that is perpendicular to a horizontal surface must be vertical. Remember, Alexander is discussing the limitations of competent and intelligent use of language to describe the physical structure of real problems. If ChatGPT and LLMs fail this badly on very basic examples, then they have no chance whatsover when faced with true design challenges.

I have been told that GPT-4 will make me reconsider my skepticism because it has been trained on an order of magnitude more data. I do not expect that to happen, and even if the next iteration of ChatGPT captures context-sensitive assertions with more plausible degrees of granularity, the fundamental issue remains, because this limitation applies to the very human language ChatGPT is designed to regurgitate.

It is perhaps worth adding, as a footnote, a slightly different angle on the same difficulty. The arbitrariness of the existing verbal concepts is not their only disadvantage, for once they are invented, verbal concepts have a further ill-effect on us. We lose the ability to modify them. ... once these concrete influences are represented symbolically in verbal terms, and these symbolic representations or names subsumed under larger and still more abstract categories to make them amenable to thought, they begin seriously to impair our ability to see beyond them.

A simplified implication of this: when all you have is a (conceptual) hammer, everything looks like a (conceptual) nail. The concept that helped simplify one problem and guide you towards a solution prevents you from seeing the real structure of another. Language models double down on this problem by reifying the symbolic relations present in its training dataset into "knowledge."

Caught in a net of language of our own invention, we overestimate the language's impartiality. Each concept, at the time of its invention no more than a concise way of grasping many issues, quickly becomes a precept. We take the step from description to criterion too quickly, so that what is at first a useful tool becomes a bigoted preoccupation.

Does this sound like the way a large language model describes the world?

Meaning and Language Models

It seems extremely basic to point this out, but human cognition is not limited to a linguistic and symbolic dimension. We have other senses: visual, proprioceptive, auditory, tactile, spatial. Perception preceded language in our evolutionary history, and experience of the world - visual, auditory, or otherwise - forms the bedrock foundation of linguistic acquisition. Even people who might struggle to form a mental picture of the nail and the wall or verbalize the concepts can still learn to hammer a nail into a wall by observing the world and interacting with it. Ignoring the non-verbal dimensions of thought leads you to absurdities like this assertion by Sam Altman:

In characterizing thought this way, he has leapt headfirst directly from description to preoccuptation. Does human reasoning and imagination sometimes involve recombination of words and symbols in context-sensitive but sometimes non-deterministic and even nonsensical ways? It would be absurd to deny that - but I think it is far more absurd to claim that this is the substance itself of thought. We are being sold an intentionally limited view of our own cognitive capabilities in order for the chief hype man of OpenAI to convince us that his Microsoft's supercomputer will soon be able to do it better than us.

Again, I find myself in the position of having to point out the obvious in a manner that betrays my own naive humanism: knowledge is about the world, about things that are true. You cannot tell whether something ChatGPT says is true without knowing something about the world yourself. This background knowledge that everyone is bringing to the table when evaluating ChatGPT is erased by assertions that ChatGPT "knows" things.

Kieran Egan notes that even pointing towards the world is not the same thing as knowledge:

We reinforce the image of the textbook, encyclopedia, or dictionary as the paradigm of the successful knower. It becomes important in such a climate of opinion to emphasize that books do not store knowledge. They contain symbolic codes that can serve us as external mnemonics for knowledge. Knowledge can exist only in living human minds.

Justified true belief may not be a sufficient condition for knowledge, but few epistemologists I know of deny that it is a necessary one. ChatGPT lacks any kind of justificatory mechanism, and cannot have 'beliefs' in any significant sense, lacking any kind of model of the world. Its operation only predicts the next word in a sequence. Despite the degree of context-sensitivity baked into that model, it lacks even a simulacra of the basic machinery of what knowledge posessed by human beings requires, and yet is being breathlessly hyped as a universal interface to information.

Even if they continue to make advances towards a "fluent encyclopedia," the larger questions remain. Does language exist to create a dictionary or encyclopedia-like description of reality? Is the map the territory? I don't subscribe to this view of language. Language is a tool. It developed under the constraints of the human body and time, in order for us to quickly communicate information about our goals, and to form social bonds. ChatGPT's model of language was developed entirely in the absence of goal-oriented behavior, and only later had a system of goals bolted on to it in order to provide a better user experience for OpenAI's potential customers. This development was misleadingly described as an 'alignment advance', despite the fact that they had no meaningful way of describing the impact of this change on the overall safety or truthfulness of the system.

We are too easily impressed by the technical feats involved in building a model like GPT-3 and too quickly forget that our knowledge arises from embodied perception, experience of the world, and successful communication with other speakers of language to coordinate and land on mutual understanding. These skills are not reproduced in any form by word sequence predictions. OpenAI will eventually learn a lesson that all mature people must: it may be far easier to repeat what other people are saying than to discover the truth, but ultimately you cannot avoid the latter.